Back in 2019, I set out to read all the new novels about the Trojan War, focalised on the perspectives of various ‘silent’ women in the Iliad. I didn’t get very far, because though I found it an interesting enough exercise, they left me rather cold. This is not because I’m some sort of Homeric purist – where, after all, would Greek tragedy have been without those slices from Homer’s banquet? – they just weren’t much to my taste.

One that stood out for me, however, was Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls, not only because I love Barker’s prose, but because I felt that she was doing something much more ambitious than simply exploring the ‘silence’ of the slave women. Inevitably, in the process of writing such works of classical reception, writers invoke contemporary tropes and psychological or societal ideas in order to make their narratives more accessible to modern audiences and because we cannot help but understand ancient texts through our own cultural lens, but Barker goes a step further: her narrative of Troy is permeated with the images and language of First World War literature. And just as the Iliad functioned as a foundational narrative in ancient Greek societies, so the First World War has a similar foundational status in our (British) society today.

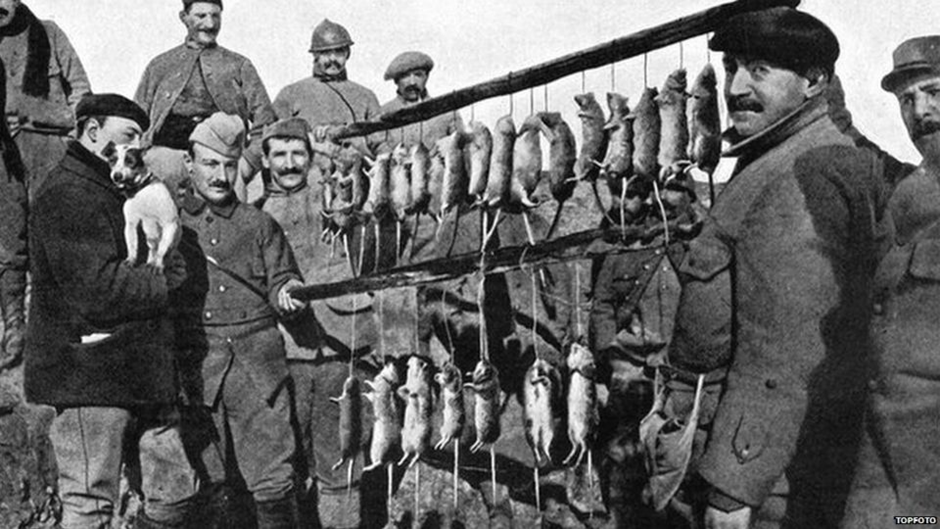

When I first picked up The Silence of the Girls, several people warned me to watch out for the rats. Even before Apollo’s plague hits the Greek tents and the rats are the first to swell and die, Barker describes the camp’s rats in grotesque detail. There were ‘Rats everywhere’ a result of the huge quantities of ‘meat and grain wasted, half-eaten food left lying around’, so many of them in fact that ‘suddenly the ground ahead of you would get up and walk’. She also describes ‘rat-hunting contests’ among the younger warriors and ‘young men strutting about with rows of little corpses impaled on their spears.’ Though the word ‘spears’ keeps us just about rooted in Troy, rats are such an iconic image in First World War literature that this cannot be coincidence. They are everywhere, as indeed they must have been in the trenches. David Jones, in In Parentheses, for example describes the sound of the sound of no-man’s land, while on guard duty, silent but for the ‘scrut, scrut, sscrut’ of the rat, as he attempts to ‘rustle’ our ‘choicest morsels’ and ‘night-feast on the broken of us’.[1] In Robert Graves’s autobiographical Goodbye to All That, he tells of rats that came up from the canal and ‘multiplied exceedingly’ as they fed on the ‘plentiful corpses’.[2] One new officer even awoke to find ‘two rats on his blanket tussling for a severed hand’. Rats also feature in All Quiet on the Western Front, as menaces who steal the men’s food, eventually reducing them to lying in wait with their spades and clubbing them to death, hurling their bodies over the parapet.[3] While Isaac Rosenberg, more philosophically, uses the rat’s ‘cosmopolitan sympathies’ to explore the horror of war for both the English and the German soldiers, their ‘heart[s] aghast’.[4] The photograph below, too, shows a group of French soldiers showing off the spoils of their terrier’s fifteen minute rat hunt in their trenches in 1916, just like Barker’s young men displaying their ‘rows of little corpses’.[5]

There is something about the physicality of Barker’s descriptions in The Silence of the Girls which chimes both with the Iliad and with First World War literature. Though there are no rats described in the Iliad, Homer is as graphic in his descriptions of the injuries the men sustain in battle as Barker or any of the writers of the First World War. W. B Yeats famously excluded Owen from The Oxford Book of English Verse on account of the fact that he was ‘all blood [and] dirt’ and we might immediately think of Owen’s description of the gassed man in ‘Dulce et Decorum est’ whose ‘blood c[a]me gargling from froth corrupted lungs’ as evidence of this.[6] However, in only one small part of Achilles’s aristeia alone, Homer describes: how Achilles’s spear went straight through Polydorus and ‘came out by the navel’, causing him to catch his bowels in his hands as he ‘sagged’ and fell to the ground;[7] how Achilles stabbed Tros in the liver as reached to supplicate him, ‘so that the liver was torn from its place, and from it the black blood’ poured;[8] and how Achilles beheaded Deukalion, and ‘the marrow gushed from the neckbone’.[9] Barker draws from this directly; as Achilles and his army overcome Briseis’s husband’s forces, she describes how Briseis watches Achilles ‘thrust his sword upwards into the pit of a man’s belly’ and ‘Blood and urine spurted out’ while the man, like Polydorus, ‘cradled his spilling intestines’.

What is really interesting for me, however, is the way that Barker deals with the treatment of injuries in The Silence of the Girls. While in the Iliad, Machaon, the healer, treats the wounded on the field and once, Patroclus treats Eurypolos in his tent, Barker transports Machaon and his traditional healing remedies of herbs and poultices, to tents which seem the equivalent of First World War field hospitals. She describes, for example, ‘influx of wounded, followed almost immediately … by another’, the women dressing wounds and passing round painkillers and both the way ‘the men laughed and joked’ during their treatment and also ‘the shouts and screams from some of the patients: men who were trying to claw their bandages off – as, in delirium, many did – and had to be forcibly restrained.’ Her descriptions are reminiscent of those in, for example All Quiet on the Western Front. Just as Barker’s hospital has a ‘stink hut’, Remarque’s has a ‘Dying Room’ – much the same thing as ‘Nobody who went into the stink hut ever returned.’[10] Remarque too describes the comradeship of the men in the hospital, who, for example, share a joke about the man who owns up to throwing a bottle because he has a shooting licence, which means ‘he can do just whatever he pleases’ but also the ‘pain and fear, groans and death gurgles’ of the ward.[11] In her passage on the ‘hospital’, Barker even refers to the warriors as ‘the men’ and to the ‘kings and captains’ as ‘the top brass’, in the quintessentially First World War vernacular.

By using these tropes of First World War Literature, Barker is not only making the experience of war more understandable for a modern readership but conveying to us something of the status which the Homeric narrative had in ancient Greek society. Both the Iliad and the Odyssey, together with the wider myth cycle of the Trojan conflict, functioned as foundational narratives, providing the basis for religious, social and political practices throughout the Greek world, not to mention its cultural memory. I will only address one small part of this here and that is the use of graphic imagery to describe wounds in the Homeric texts, which I have already cited above. Johannes Haubold writes of ‘Homer’s ability to depict a scene so gruelling that we would not want to witness it directly’ and that such vivid detail is a quality ‘to reflect on and worry about’.[12] This became very clear to me in the live reading of the Odyssey, staged and broadcast by the Almeida Theatre in 2015. While Odysseus’s brutal murder of the suitors in Book 22 is a fast moving scene on paper, and the eye moves quickly over the details of the slaughter, hearing the episode read aloud was a very different experience. The details of snapping tendons and bones, gushes of blood and the ripping off of genitals are relentless and horrifying. And this is the glorious apex of the poem, the hero’s reclamation of his wife, his home and his kingdom. The same is true of Achilles’s aristeia in the Iliad, in which on the one hand we see the hero’s valiant return to the battlefield but on the other, we see his bestial nature, made explicit in the animal imagery of the scene and culminating in his wish ‘to hack [Hector’s] meat away and eat it raw’.[13] The Homeric texts use vivid details to represent tisis, or the violent repayment of wrongs done to one, as highly problematic, and this was something which Athenians at least, remembered, together, annually at the festival of the Panathenaea.[14] In addition to this, because the Trojan War represented, for them, a kind of foundational trauma, which ‘abruptly dislodged’ the ‘patterned meanings’ of the society of their forebearers, the annual remembrance becomes a part of a continual struggle, a collective striving, for something better.

I cannot claim any kind of expertise in First World War scholarship, but it has always seemed to me that the First World War functions similarly in British society today, and this belief is supported by a branch of scholarship in the wake of Paul Fussell’s seminal work The Great War and Modern Memory. The First World War operated as a kind of collective trauma for British society at the time, redefining the way in which society saw itself and banishing the Romantic in favour of the Modernist.[15] Geoff Dyer quotes Wyndham Lewis as describing World War One as ‘the turning point in the history of the earth’, but that ‘By ushering in a future characterized by instability, and uncertainty, it embalmed forever a past characterized by stability and certainty.’[16] This is not to say, as Fussell explores at length, that society was actually substantially different, but that the perception of this ‘fact’ took hold in such a way that we can speak about this in terms of a collective, communicative trauma. More than this, however, the root of this perception came not from the experience of the war, but from ‘the elaborately entwined, warring versions of memory in the decade and a half following the cessation of actual hostilities’, and in particular, the literature of the war which had such an eye to its own commemorative function.[17] Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ stands for the death of a certain kind of upper class, chivalric Englishness which had dominated our perceptions of identity and empire, and as such, it seems ‘invisibly appended, like exquisitely engraved graffiti, to memorial inscriptions in honour of “The Glorious Dead”.’[18] And Owen’s vivid descriptions – his ‘blood…gargling from froth corrupted lungs’ perform the same kind of function as Homer’s: they force generation after generation to question whether this is something we ever want to see again in our world.

Like the Trojan War stories for ancient Greek societies, the poetry of the First World War is ingrained in us, often from our primary school days, as the ultimate example of the horror and ‘pity of war’. Indeed, many children first study the War through its poetry and certainly the poetry is what leaves the strongest mark on the imagination. Remembrance Day is the most significant (and only?) cross-cultural national day of remembrance in the British calendar. Although the definition of those whom we remember on this day has broadened over time, the occasion is still dominated by its First World War origins and Laurence Binyon’s poem, ‘For the Fallen’. There cannot be many of us unfamiliar with the lines ‘At the going down of the sun and in the morning / We will remember them.’

In conflating the First World War with the Iliad, then, Barker gives us an experience of the Trojan War which seems real to us because of our familiarity with the tropes on which she draws. More than this, though, she conveys to us something of the collective, foundational trauma of the earlier text and of the way in which it functioned in Greek societies, drawing them together in communal acts of remembrance and helping not just to inform, but to reinforce, through a process of constant questioning, the political and moral structures of the age.

[1] David Jones, In Parentheses (Faber and Faber: London, 1937, this ed. 2010), p. 54.

[2] Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That (Penguin Books: Harmondsworth, 1957; first published by Jonathan Cape, 1929).

[3] Erich Maria Remarque, trans. A. W. Wheen Fawcett Crest, All Quiet on the Western Front, accessed as an online pdf on 02/01/20 at all_quiet_on_the_western_front.pdf (weebly.com), p. 46.

[4] Isaac Rosenberg, ‘Break of Day in the Trenches’, accessed on 02/01/20 at Break of Day in the Trenches by Isaac Rosenberg | Poetry Magazine (poetryfoundation.org).

[5] BBC Bitesize website, accessed on 02/01/20 at How did animals help in World War One? – BBC Bitesize.

[6] Wilfred Owen, ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’, accessed on 03/01/20 at Dulce et Decorum Est by Wilfred Owen | Poetry Foundation.

[7] Richmond Lattimore trans. The Iliad of Homer (The University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London: 1951), 20. 416-18.

[8] Ibid. 20. 469-70.

[9] Ibid. 20. 482-83.

[10] Remarque, p. 122.

[11] Remarque, p. 121 and 125.

[12] Johannes Haubold, “Beyond Auerbach: Homeric Narrative and the Epic of Gilgamesh,” in Douglas Cairns and Ruth Scodel (eds.), Defining Greek Narrative (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), pp. 13-28.

[13] The problematic nature of tisis is discussed in Barbara Graziosi and Johannes Haubold, The Resonance of Epic (London: Bloomsbury, 2005), pp. 131-32.

[14] There is much excellent scholarship on the Homeric texts as foundational narratives. If you are interested in reading more, you might look at: Graziosi and Haubold, as in note 13; Elton T. E. Barker, Entering the Agon: Dissent and Authority in Homer, Historiography and Tragedy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009); or my own thesis, particularly pp. 98-105, which you can find here: Raudnitz – Thesis.pdf (open.ac.uk).

[15] For the theory of collective trauma see Jeffrey Alexander et al., Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

[16] Geoff Dyer, The Missing of the Somme (New York, 1994), p. 5.

[17] Ibid, pp. 16-32, quotation on p. 32.

[18] Ibid, p. 32.

Excellent.

LikeLike

Fabulous with a tinge of disappointment.

Loved this a read but disappointed because, and I feel fairly experienced, that I did not make any of these connections which feel now so obvious. I have diffulty it seems on getting past the characters to look at the reasons behind the scenes. I guess the more I read the more chance I will have to appreciate parallels. The nearest I got to modern day with the rat scene was evoking the urban myth that you are never more than 6ft away from a rat with the final words that they were like kebabs – who doesn’t know what a kebab looks like?

Anyway, I loved reading this thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Classicalstudiesman and commented:

Excellent analysis, argument and read

LikeLike

I so enjoyed reading this — very thought-provoking and an outstanding read- so thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks, I’m glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike